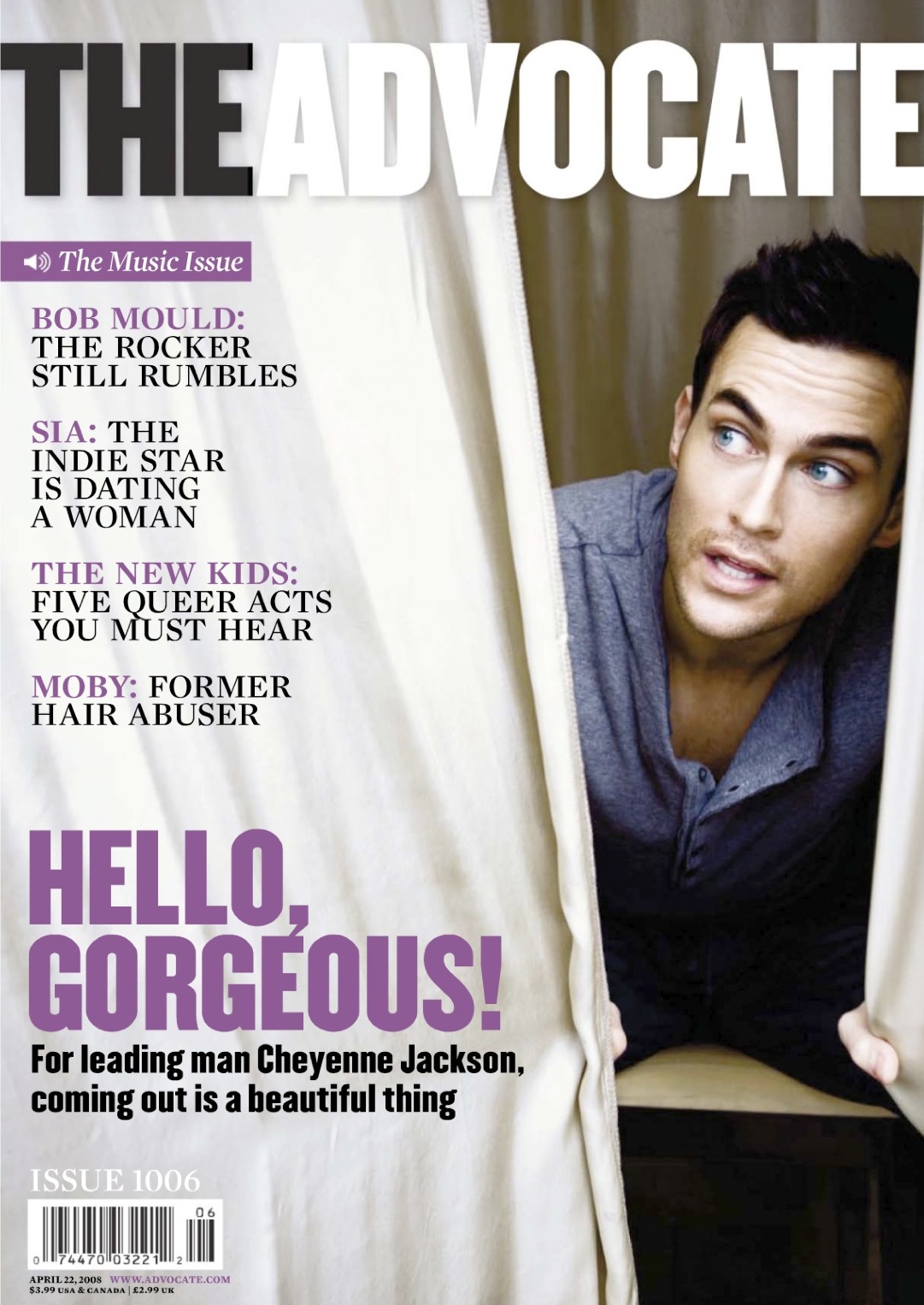

Most leading men are afraid to be out and proud. Cheyenne Jackson is bigger than that.

By Brandon Voss

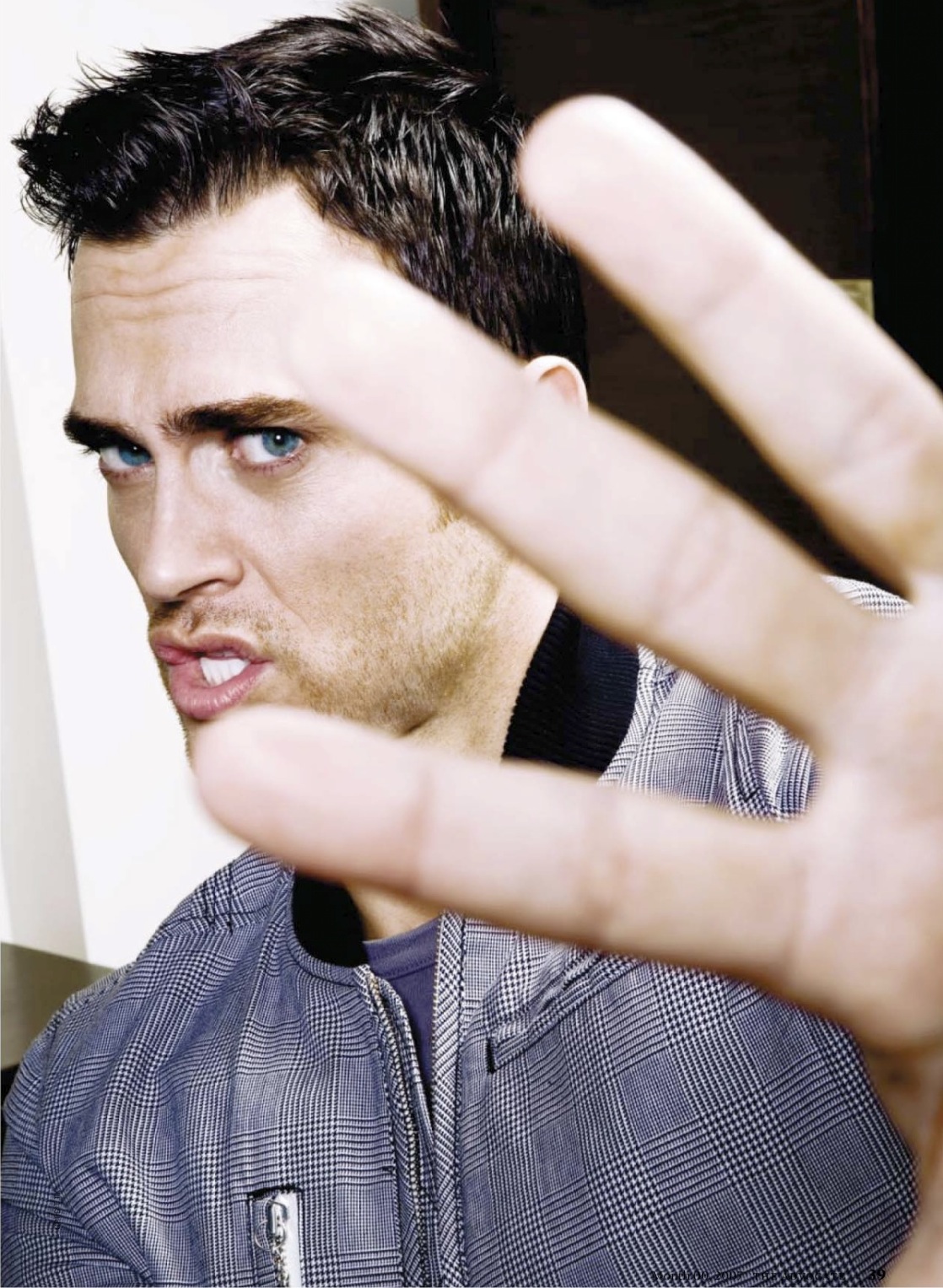

“I’ve actually never talked about this before because it’s a little bit twisted,” whispers Cheyenne Jackson across a corner table at Sardi’s in New York City, where a caricature of his handsome head has just been added to the restaurant’s estimable walls of fame. “The first time that I knew I was gay — I think I was, like, 7 — I was watching this Valentine’s Day Popeye cartoon episode that would play every year. There was this scene where Popeye was captured by Brutus, tied up with no shoes or socks on, and Brutus starts tickling his feet. I remember getting a little boner, and I didn’t know what it was about that scene that was creating that, but I knew that it was something naughty that I couldn’t tell anybody, and I definitely knew it was something that made me different. But every year, I couldn’t wait for that episode.”

Jackson’s publicists would probably prefer that he hadn’t shared that anecdote; in fact, as was made clear to me before our interview even took place, they would prefer that this article not focus on his being gay at all. Too bad that’s all I want to talk about. “We’ve had this conversation over and over,” says the actor with a chuckle, sipping a Grey Goose and soda with a splash of orange juice. “I said, ‘It’s The Advocate. I have to talk about my sexuality.’ But it’s their job to say, ‘Don’t only talk about guys you’ve hooked up with!’ They just don’t want me to be pigeonholed, because they want me to have as many opportunities as I can.”

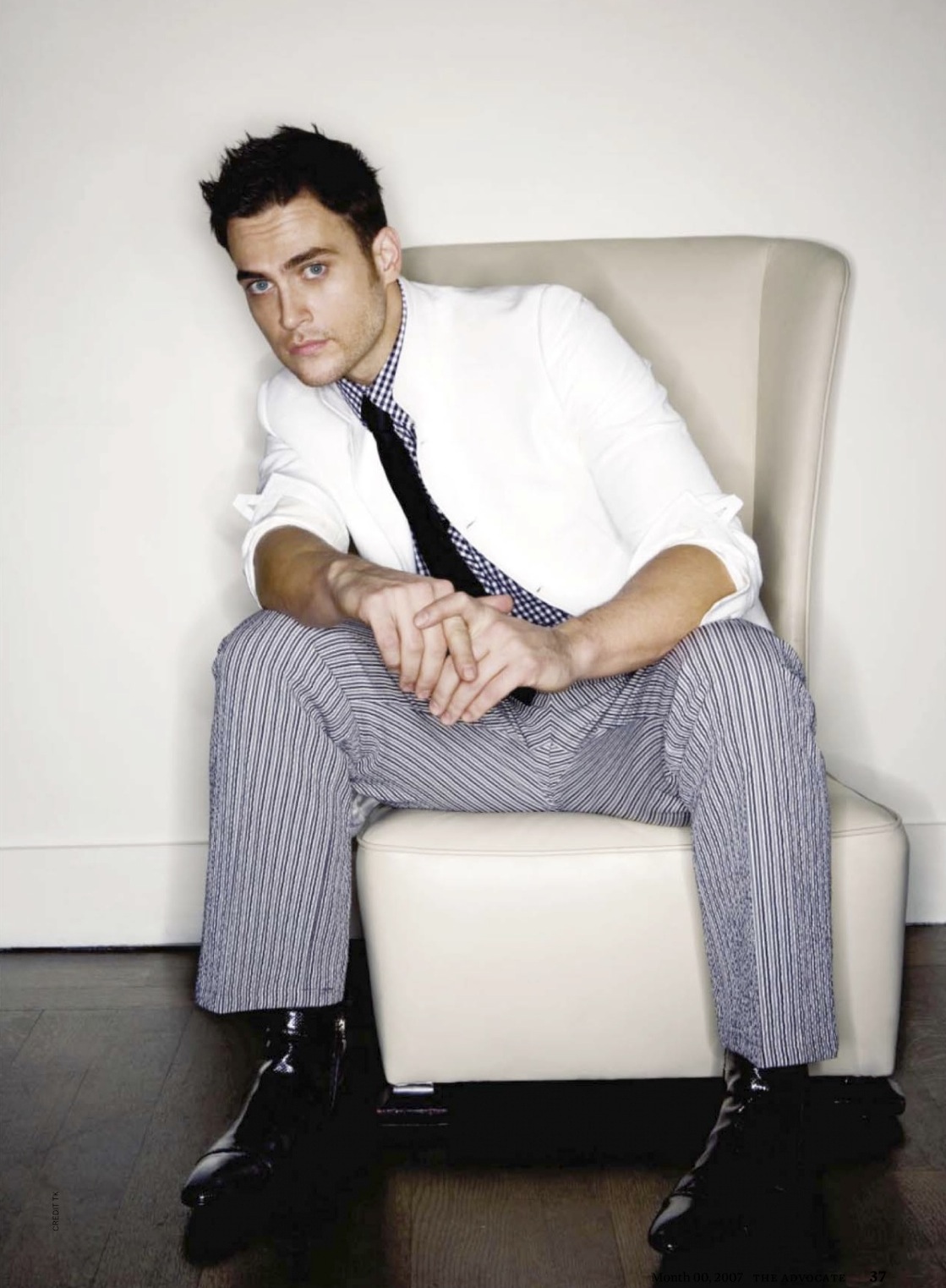

Now starring as struggling artist Sonny Malone in Broadway’s campy hit musical Xanadu (based on the 1980 roller-disco cult movie starring Olivia Newton-John) through July, Jackson came out professionally in The New York Times not long into the run of All Shook Up, a 2005 Elvis jukebox musical in which he made his breakthrough as the Elvis-like lead. “It wasn’t something I planned on doing,” he recalls, “but I’ve been out to my family since I’m 19. The interviewer kind of said, ‘And you’re gay, right?’ I didn’t even think about it and said, ‘Yeah.’ I could’ve, in a frenzy, had people call him to retract it, but I thought, Let’s see what happens. People worry about someone who’s an up-and-comer and so open about it, but I feel like if I don’t make it an issue, it’s not going to be an issue.”

Though Jackson has never regretted his decision, he’s pretty sure his agents have. “To be frank,” he says, “I think I’ve missed out on big parts because I’m open. I’ve screen-tested on some really big projects, and you can’t tell me that behind closed doors big execs aren’t like, ‘We have Dean Cain or this gay guy who played Elvis on Broadway.’ I’m not that naive to think that that doesn’t play into it.”

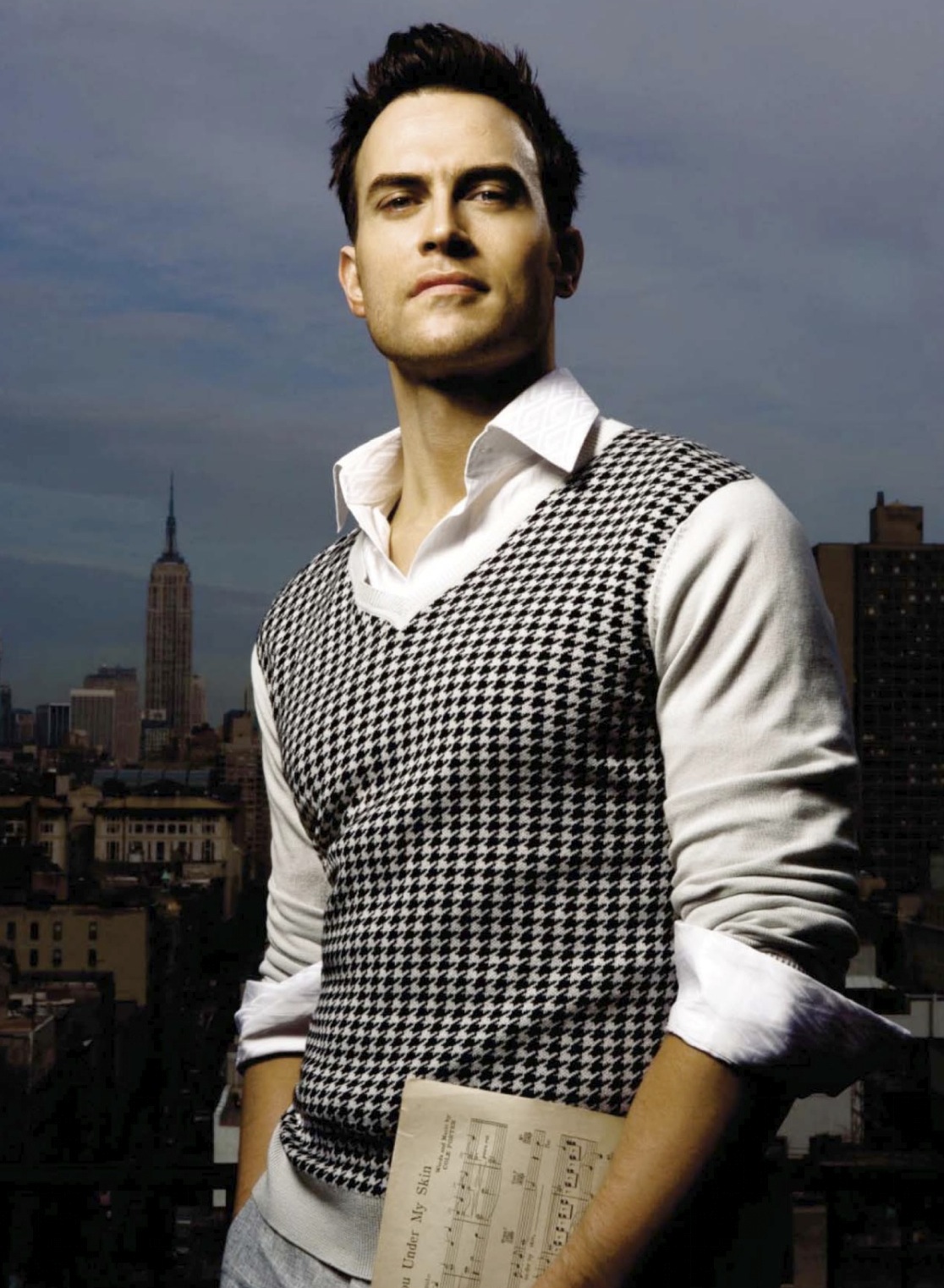

Conveniently, Jackson says he has no aspirations to be the next Brad Pitt; he just wants to work regularly on quality projects. His well-known sexuality didn’t prevent him from landing the role of the womanizing son in the Lifetime pilot Family Practice, costarring Anne Archer and Beau Bridges, although he learned on the day Heath Ledger died that the show hadn’t been picked up. (“So it was a really bad day,” he says.) The 6-foot-4 tower of muscle also stars in the upcoming thriller Hysteria, in which his character’s wife, he brags, is played by “hot little mama” Emmanuelle Vaugier, a Maxim cover girl. “I’m in uncharted territory because based on what I look like, I get cast as the guy who gets the girl. But I have a sense that the tide is changing, and I have no problem being the trailblazer. I don’t know how or when it’s going to manifest itself, but I think being my authentic self is going to have its rewards.”

Perhaps sooner than later: “Buzz and movement,” he says, have already begun following a recent Variety.com interview in which he expressed interest in portraying famously closeted icon Rock Hudson on the big screen. “My Xanadu costar Tony Roberts knew Rock Hudson, and he said, ‘You remind me of him in so many ways; not just physically, but your spirit and sense of humor.’” But Jackson’s quick to note his fundamental difference with Hudson: “Just think of all the people back then who couldn’t be themselves and all the wonderful things they could’ve created. When you live in fear, it’s got to weigh on you.”

The only weight that’s been placed on Jackson’s broad shoulders the last few years has been one of responsibility to the LGBT community, though he seems neither frustrated nor resentful to be carrying the sequined torch while so many of his queer peers remain in the closet. “I’ve had conversations with famous people who aren’t out, and more than anything it just makes me sad. But everybody has their own journey, and I hate the whole witch-hunt aspect of outing people — a lot of which comes from the gay media,” he states firmly, specifically referring to former blog target Neil Patrick Harris. “I mean, he’s been out forever, and everybody knew that, but I guess Middle America isn’t going to believe you’re out until they see you on People magazine saying, ‘I’m gay!’”

Jackson points to his own recent profile in People as a positive example of how out celebrities should be treated in the media. “It didn’t mention my sexuality because it wasn’t relevant,” Jackson explains. “Then I got all this feedback, like, ‘Oh, is Cheyenne going back in the closet?’ It’s like, Fuck off. I don’t have time for that. ‘Openly gay Cheyenne Jackson’ is weird to me. They never say ‘openly straight Patti Lupone.’ It’s so reductive, but then when I say that the militant gays are, like, ‘Well, you’re a role model, so you should just deal with it!’ For the militant gays, you can never be out enough. I get flak because there aren’t pictures of me kissing my partner, or I don’t always say ‘my partner and I.’ I have a partner. A gay partner. We’re gay. How much gayer do you want me to be?” For the record, those who don’t think Jackson’s gay enough need only visit his dressing room — where someone has scrawled “Miss Jackson if you’re nasty” on the door — or hear him relive locking eyes with audience member Ricky Martin during a recent Xanadu performance.

Jackson still has a beef with an item that Village Voice columnist Michael Musto ran following an interview the actor had done to promote Paul Greengrass’s 2006 docudrama United 93, which was nominated for a best-directing Oscar. In United 93, Jackson made his feature-film debut as heroic gay rugby player Mark Bingham. “I said something along the lines of, ‘If my mom or wife or baby had been on the plane…’ Well, Musto heard ‘wife’ and wrote in his column, ‘Nobody asked about [Jackson’s] sexuality after that.’ It was bitchy, obnoxious, and really kind of harmful.” He pauses, then laughs, catching himself getting, well, all shook up. “That stuff clearly gets on my nerves.”

At this point I admit that I too had feared his closet retreat when another Advocate cover story aimed for Xanadu’s summer ’07 opening abruptly fell through. “That was all my old publicist that I gave the heave-ho,” he explains, blaming a strained professional relationship that began “as a blind date that someone else was paying for.” After the Advocate snub, he continues, “I fired her right away. Several people who had worked with her on other things said, ‘I think she has issues with gays,’ but it wasn’t something I knew when I first starting working with her. She’d make blanket statements like, ‘No, we’re not doing any gay press.’”

As he polishes off a club sandwich with mayo and a side of fries — yes, fries (having just seen him onstage in short-shorts and a tank top, I poke at a salad) — Jackson sums up his own love-hate relationship with the gay media and their high expectations: “Look, I’m not somebody that marches in the front of a gay pride parade, but if I wanted to, I would. I’m not a self-loathing gay; I just feel like being gay is the least interesting thing about me. But I also understand that people want to be represented, and I’m happy to be that for them — to a point.”

As a pleasant contrast to the e-mails he receives through his website from right-wing Christians warning him that he’ll “die a horrible death,” Jackson’s inbox is regularly flooded with messages from small-town teenage boys whom he’s inspired to come out. “One of them asked me to send him a picture, and he said he held it as he told his family because it gave him strength. A couple weeks later when his friend was going to come out, he let the friend hold my picture. It’s kind of heavy, but at the same time if they feel support and strength just by the way I live my life, that’s great.”

It’s a comfort Jackson didn’t have attending House of the Lord Christian Academy in his tiny, rural hometown of Newport-Oldtown on the Washington-Idaho border — “very Little House on the Prairie,” he says — where the only gays were known as “the dump dykes,” two mullet-sporting lesbians who ran the local garbage dump. “The school would quote Scripture — ‘It is an abomination in the eyes of the Lord to lie down with another man’ — and I was told that I would be going to hell, so from a very young age I knew that it was something that I would have to deal with later in life.”

Though Jackson always had girlfriends, his heart belonged to Chuck, his best friend in high school. “I was in love with him,” Jackson recalls. “I truly thought that we would be together. If he got a girlfriend, I’d purposely make sure that my girlfriend was best friends with his girlfriend so that we could always do shit together. He was a Mormon, and right before he left on his mission, I took him to lunch and said, ‘Chuck…’ And he said, ‘I know. I’ve always known.’ And I was like, ‘You have? Oh, my God!’ To this day, he’s still a friend, but now he’s married and has five kids.”

With no matinee idol’s head shot to clutch, Jackson didn’t find it quite so easy coming out to his family at age 19. “We called a family meeting,” he recalls, “and I said, ‘Well, I think families should be close and know everything about each other, so it’s time that you knew I was gay.’ ” Met with both shocked silence and sobbing, his brother began reading a letter Jackson had written detailing his journey and first memories — “but not the Popeye memory,” he adds. After his bomb’s fallout dissipated, he and his family didn’t discuss the topic for about two years. “I just separated myself from them. I realized that they had to mourn their ideas of what they thought my life would be. I wasn’t going to be the first to have kids, which they’d always thought, because I was a Sunday School teacher and the only guy on the block that babysat. So I had to give them time.”

Southern California hippies before moving North and becoming born-again Christians, Jackson’s parents encouraged him to enroll in the ex-gay organization Exodus International but didn’t belabor the issue. “They’re people that you’d look at and think, Oh, they’ll never come around, but they did. I’m not saying they’re voting for Hillary Clinton, but as they’ve gotten older they’re swinging the pendulum back a little bit.” His brother, a pastor for a large nondenominational church and a regular preacher on The 700 Club, has been a harder shell to crack. “He thinks that being gay is something that can be prayed away, or that maybe you didn’t have strong male influences growing up — which couldn’t be further from the truth for me, because my father is a Native American Vietnam vet, and we were very close. I love my brother dearly, but it’s come to a point where we just don’t talk about religion or politics. It’s the only way that our relationship can work.”

The whole family is, however, warmly accepting of Monte, Jackson’s partner for almost nine years, a medical physicist he met in Seattle and moved in with three weeks later. “It was very lesbian,” Jackson jokes, “but we just knew.” Though they plan on becoming parents, neither feels the need for marriage to validate their relationship. “Some of our best friends have done the full-on wedding with invitations and tuxes, and that’s perfect for them, but we already feel like we’re married. He’s my very best friend, and it’s a great feeling when someone gets you and will always be there. I’ve never experienced that before. Do I want to knock his block off sometimes? Sure.”

While their domestic dramas typically deal with cleanliness and tardiness (“I’m not a slob, but it doesn’t bother me like it does him if there are dishes in the sink when we go to bed; if we have to be somewhere in 15 minutes, he’s changing clothes, lagging around, and it drives me crazy!”), jealousy is not a source of contention, despite how groupies of both sexes often slip the star their phone numbers after the show. “Sometimes I actually try to make him jealous,” Jackson admits. “There was this beautiful Italian man by the stage door once while I was out signing autographs — I mean, he looked like a postcard from Capri. After I took a picture with him, he talked to his friends and then pulled me back and said, ‘There you are, back in my arms where you belong.’ I told Monte that story, and he was, like, ‘Lovely. Unload the dishwasher.’ He couldn’t give a shit. He knows who I’m going home with.”

Should the American Theatre Wing and Broadway League see fit, Monte also knows whom he’ll be with at the Tony Awards ceremony on June 15 — whether or not there’ll be photographic evidence to prove it. “He just hates any kind of focus on him,” Jackson says. “People try to grab him on red carpets, but he ducks out, and all you’ll see is his arm. But if I get nominated for a Tony, he’ll be sitting right beside me, and the camera will be right there, so I don’t think he’ll be able to get out of that one!” And if Jackson hears his name called as winner, will he prove those pesky militant gays wrong by going in for a nationally televised lip-lock? “If the spirit moves me, yeah, why not?”

The Advocate, April 2008.