Playwright Chris Urch on why The Rolling Stone has universal appeal.

By Brandon Voss

In 2010 a Ugandan tabloid newspaper, Rolling Stone, published the names, photos, and addresses of suspected gay locals under the banner headline “Hang Them.” LGBTQ activist David Kato, among those listed in the article, was brutally murdered a few months later in his own home.

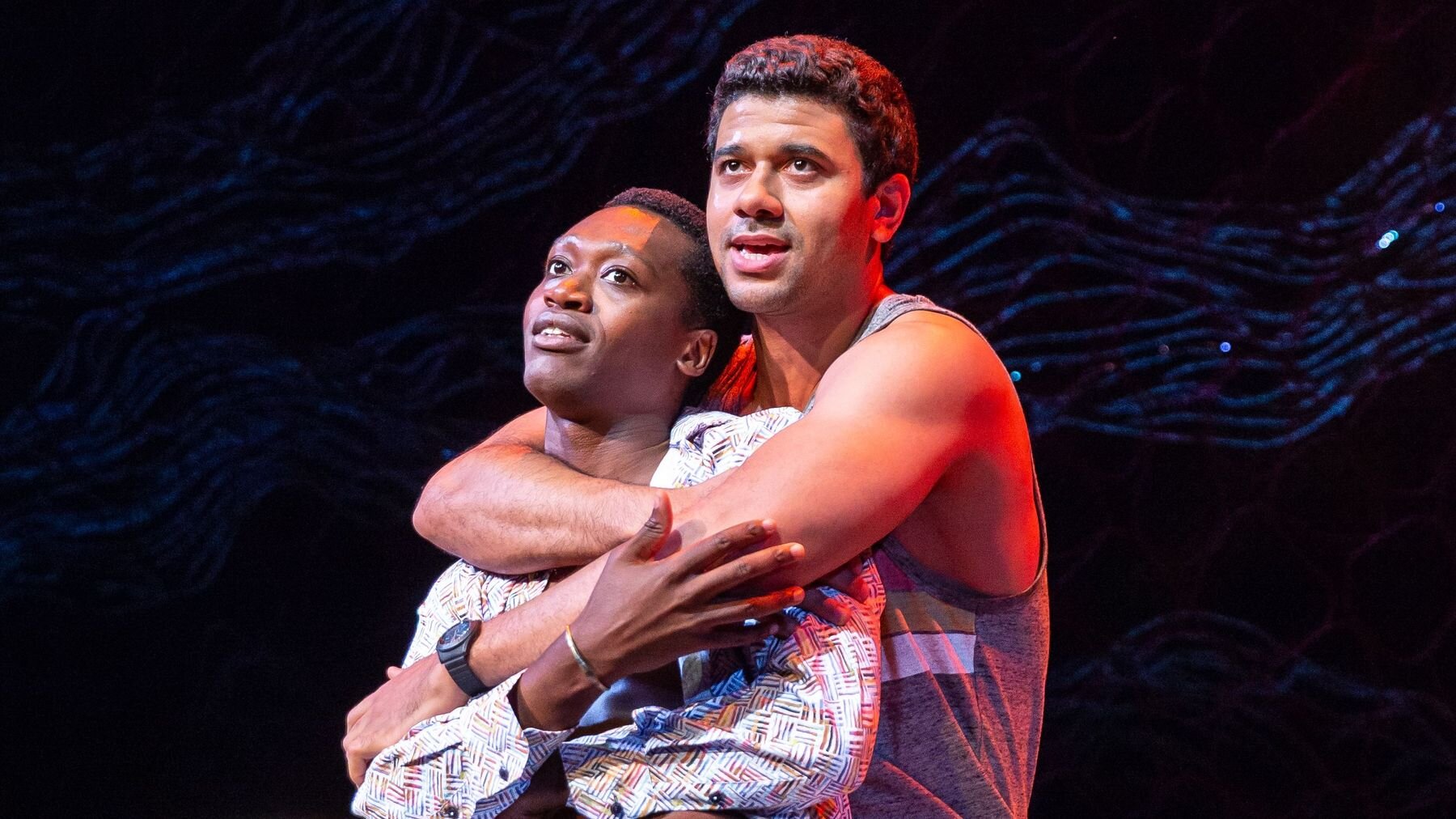

Inspired by the mass outing, gay playwright Chris Urch’s family drama The Rolling Stone finds two Ugandan brothers at odds: Joe (James Udom), a homophobic pastor, and Dembe (Ato Blankson-Wood), a closeted gay man secretly dating Sam (Robert Gilbert), a half-Ugandan doctor from Northern Ireland. The play now makes its American premiere off-Broadway with a Lincoln Center Theater production helmed by queer director Saheem Ali, who was raised in Kenya.

While homosexuality was accepted in pre-colonial Ugandan society, anti-gay laws were introduced when Uganda became a British colony. A Ugandan bill adding the death sentence as a penalty for gay sex, signed into law by President Yoweri Museveni, was ruled unconstitutional in 2014; however, consensual homosexual activity remains a crime punishable by incarceration, and LGBTQ Ugandans face ongoing abuse and intimidation.

Visiting New York for The Rolling Stone’s opening, Urch spoke to NewNowNext about what business a white British writer has taking on Ugandan politics.

NewNowNext: You’ve had great success with The Rolling Stone in the U.K. and around the world. How does it feel to finally have the show produced off-Broadway?

Chris Urch: It’s a huge honor, and it’s been an absolute dream come true. Most British writers would be lying if they said they didn’t want their plays produced in America. Any writer wants their work to touch as many hearts and minds as possible.

When you read about what went down in Uganda, why did you want to tackle that story for the stage?

I thought what that paper had done was so disgusting. I felt really angry. I don’t want to compare my experiences to anything in Uganda, but as a British gay person from a small village, I’ve faced discrimination, as most gay guys have. I’ve faced physical violence. I’ve had to question holding my boyfriend’s hand in the street, even in London. So the more I read, the more research I did, I became obsessed with the story and with David Kato, who was murdered due to being listed by that paper. Sometimes the best thing to come out of anger is passion.

It’s important to note that homophobia in Uganda stems from British colonial laws and American evangelical missionaries, so both of our countries are complicit in the anti-gay violence there.

Yeah, the play raises those issues, but hopefully not in a heavy-handed way. I view politics through the personal, and I was coming at it from a British point of view. I felt sick that we are responsible, that these homophobic laws are part of the British colonial heritage. But when I first started writing the play in 2012, the world was a very different place. I find it really scary, especially as a gay man, to see the rise in homophobia, intolerance, and hate crimes in America and the U.K.

The play somehow manages to avoid portraying those with homophobic views as villains.

This is not a play saying that Ugandans are bad or wagging a finger at those characters. With every character, even if you don’t agree with them, I want you to be able to understand them. It’s important for me to create characters that are three-dimensional — and to give actors something to sink their teeth into.

It’s not hard to imagine an alt-right American website publishing a list of undocumented immigrants or LGBTQ people perceived as dangers to society. Has your play become a cautionary tale in the Trump era?

Audience members bring themselves into the play, and if that’s something they get out of it, sure. I’d like to think the play raises a lot of questions. Fundamentally, the play is about how far you’ll go for the people you love. If you find out someone you love is all those things you’ve been brought up to believe are wrong, how do you deal with that? How can we have differences and put them aside to get along? It’s complicated.

Why did you fictionalize the real events in Uganda through the lens of a family drama and a love affair?

Because that’s what’s universal. We all have some form of family, and most of us, if we’re lucky, have had a loving relationship. When looking at a another culture, we need something we can all relate to, characters we can empathize with. So that felt like the right way into this particular story.

Because you are exploring a different culture, did you question whether you were the right person to tell this story?

Yeah, I did. I really wrestled with that. But I felt that the British influence was my way in, especially with the character of Sam, Dembe’s boyfriend, who is half-Irish. And, again, regardless of culture or race, it’s about a young gay man in a relationship, and I do share that experience. If you’re passionate about a story, you should go for it. But you have to be respectful, do your research, and surround yourself with people who know better than you, to make sure you’re being sensitive. While workshopping the play, I talked to as many people as I could, people who were in Uganda at that time, to make sure we were being as authentic as possible.

Were you able to travel to Uganda?

[Laughs] Unfortunately, when I was writing the play, I was on welfare, so I didn’t have the money to travel. I was struggling to feed myself.

Could The Rolling Stone ever be produced in Uganda?

I would love that to happen. Right now, that’s not a possibility. There was a beautiful production done last year in Brazil, which has the world’s highest LGBTQ murder rate. It caused a lot of anger and discussion there, but the actors and producers believed in the play. I’m really proud that they did it.

Dembe’s faith is challenged by the anti-gay doctrine preached in his brother’s church. Does that reflect your own relationship to spirituality?

No. I wasn’t really brought up in a religious household. But a lot of actors who have played Dembe were, and we’ve had a lot of conversations about it. It’s very interesting, actually, how many of my friends have had to wrestle with what’s preached and what they believe, and it’s a really difficult thing.

From their first date to their intimate moments in the bedroom, Dembe and Sam’s relationship feels rich and specific. Was their dynamic inspired by your own romantic relationships?

Now that would be telling. [Laughs] Maybe? Possibly? But that’s lovely to hear you say. Representing gay men onstage is a responsibility I take really seriously. It’s important for me to portray everyday gay relationships in an authentic, honest way, and I hope that comes across. It’s not all about sex, six-packs, and saunas.

NewNowNext, August 2019.

Photo: The Rolling Stone/Jeremy Daniel