Director David Sigal serves up a starry, spicy slice of New York’s LGBT history in his Outfest selection Florent: Queen of the Meat Market.

By Brandon Voss

From its 1985 opening until its untimely closure in 2008 on Gay Pride Sunday due to rising rents in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, Florent bloomed as a unique 24/7 dining institution ruled by charismatic gay owner Florent Morellet, a HIV-positive equal rights and AIDS activist with a sweet tooth for throwing drag parties and posting his T-cell count above the daily special. Native New Yorker and Florent devotee David Sigal documented the iconic diner’s last months and interviewed its most famous fans in Florent: Queen of the Meat Market, which screens at Outfest 2010 — his third showing at the LGBT festival following The Look, a 2003 film about teen modeling, and Conception, a 1996 short about a lesbian couple having a baby with a gay friend. Sigal laments the empty spot Florent’s finale left on the scene and in his stomach.

The Advocate: Florent clearly meant many different things to many different people. What about the place compelled you to make a film about it?

David Sigal: I felt like this little diner in the Meatpacking District had so many stories to tell — stories about New York, activism, historical preservation, art, celebrity, culture, and how one person could really make a difference.

As someone who moved to New York in 2004, I only knew Florent as a fun joint where I could get good food after a night of drinking. But as Poz founder Sean Strub says in the film, “What Florent has meant to people with AIDS since the earliest days of the epidemic is difficult to overestimate. Much more than a restaurant, it’s a movement.” I was oblivious to the living wills printed on menus in the early years of the epidemic and Florent’s practice of posting his T-cell count on the specials board since his diagnosis in 1987. Were you aware of that history?

Not really, to be honest. I was more of a regular customer. I went to NYU film school, and those days I may’ve been a late-night customer, but in the later years I turned into more of a 7am, 8am breakfast type of guy. The more I found out about him when I started doing research, the more I felt like that there was really a story to tell here. I was intrigued with how Florent was able to use activism as a tool in business, and yet most people never really knew it because everyone was having so much fun. It wasn’t heavy political activism because he did it so tongue-in-cheek, and I admired that. You’d think that a restaurateur coming out as HIV-positive might’ve turned some people off, but I’ve never heard anything negative like that, and I must’ve talked to 300 people. He took a lot of risks and chances, but nothing really seemed to have backfired.

But you didn’t know that the restaurant would be closing due to the landlord’s drastic rent increase when you first started filming.

Not at all. I knew him casually through mutual friends. I knew people in local community politics — my partner of 17 years is on the community board with Florent — so I mostly knew him through them, and I would talk to him. He’s a really warm guy with so many stories, so I called him on the phone, gave him a little idea of what I wanted to do, and he said, “Let’s get together and talk.” I went over to his apartment one morning, and I just happened to bring my little camera with me. He immediately agreed, so we started filming that second. There’s one scene in the movie that’s from that initial meeting where he shows me his grandmother’s cookbook. And off we went, and we kept talking for six months. Around halfway through, about March or April of 2008, I found out the restaurant was going to close, so we were there to document those last five weeks, including the last night the restaurant was open.

So you didn’t really have an ending when you started shooting? It’s just hard to imagine the film without that cathartic closure of this great chapter in New York history.

I don’t think it’s unusual for a documentary to not really know where the film is going to go, but you’re right — the closing was good for me and the documentary but bad for New York City. I was extremely conflicted about it.

Were you worried it might be impossible to adequately convey the special magic of the place to your audience? A Florent regular might say, “You really just had to be there.”

Before I started filming, maybe, but then what happened was that every single person I asked to talk for the film said yes. Everyone from Robin Byrd to Diane von Furstenberg — they were all eager to do it. It was so easy for me to arrange these interviews because people wanted to speak about the restaurant, and everyone had a different idea of what it meant to them.

Julianne Moore was quite a get. How did you manage that one?

It was nothing. I’m on the board of an AIDS advocacy and research organization called TAG, which is Treatment Action Group. She was at a benefit one evening. I just asked her, she said yes, and I went to her apartment and filmed her. If you listen really closely to that interview you can hear her kids playing in the background. She had quite a long history in the neighborhood. During one of her first photo shoots, she used a Florent bathroom as a changing room, which I thought was really funny. We were able to find that photo and put it in the film.

She’s probably the sanest person you spoke to, and I mean that in the nicest way possible. You got interviews with the kookiest characters in the downtown New York nightlife, art, performance, and fashion scenes. Who was the most fun to talk to?

Isaac Mizrahi was really funny, and I feel really lucky to have gotten an interview with Christo and Jeanne-Claude before Jeanne-Claude died. But there was a longtime hostess named Darinka Chase — the one with the beehive? She’s just incredibly charming on camera, and people love her perspective and how smart she is. There are so many interesting, wacky folks in the doc, so I hope that in 30, 40 years, this movie will be like watching a time capsule of a certain place and time like those Warhol films.

Tell me about the first time you showed the film to Florent Morellet.

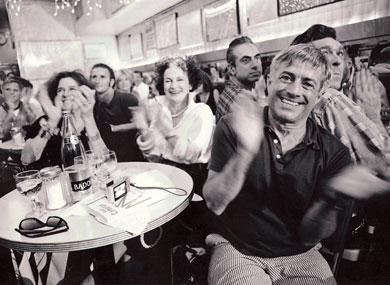

I showed the film as a work-in-progress at NewFest in June 2009 because I was eager to get some audience feedback. That was the first time I showed the film to Florent. It didn’t even have credits because it was definitely a rough cut, but when the light went on in the theater, I saw that he was crying. So I knew that we did pretty well, and then we wound up winning the Audience Award for Best Documentary. He gave me some factual feedback and suggestions, but overall he was a great subject because he pretty much stayed out of it.

You recently premiered the final cut at the New York City Food Film Festival. What was the experience like?

We won Best Film at that festival, and Mayor Bloomberg presented me the award, so that was a great experience. It was also great because so many people from the restaurant were there, so every time a host, a server, or any past employee came on screen, people started applauding.

The film points out Florent’s eclectic mix of patrons — blue-haired old ladies, blue-haired punks, and everyone in between. But no matter who was there on any given day, the LGBT community was always a strong presence. There’s even a funny sequence in the film where practically everyone independently recalls the abundance of “tranny hookers” in the early days. Why did the LGBT community feel so at home there? Was there more to it than the fact that the owner was an openly gay AIDS activist?

If you go back to the mid-’80s and the early ’90s, the era before the Internet, this was a place where people could really meet and pass on information, especially with regards to AIDS and activism. People could go to Florent and organize political action, such as the bus trips to D.C. for pro-choice and gay rights.

Do you feel that your being gay helped endear you to Florent?

Yeah, but I always felt it was more eclectic than just the gay crowd. It reminded me of Warhol’s Factory, where you had artists, celebrities, socialites, and everyday wacky New Yorkers, so it felt more than an LGBT clubhouse. It really was a mix, which is what made it so special.

Where do you eat your breakfast these days?

I’ve been craving a good place to get my breakfast now, so it’s funny you should ask. I don’t have a place that has replaced Florent in New York City. Everyone jokes that the closest equivalent is Tortilla Flats, but I don’t go there for breakfast.

Advocate.com, July 2010.